Queen Emma

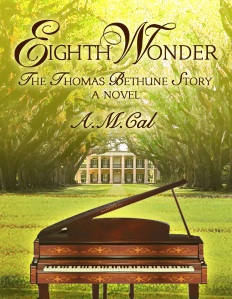

While working on my novel Eighth Wonder this morning, I discovered I needed to research some information on Mark Twain, and during the course of my internet surfing I came across this fascinating royal, whom Mark Twain met and wrote about in an article published in an antebellum Hawaiin newspaper.

Life

Early years

Queen Emma was born on January 2, 1836 in Honolulu and was often called Emalani (“royal Emma”). Her father was High Chief George Naʻea and her mother was High Chiefess Fanny Kekelaokalani Young.[1] She was adopted under the Hawaiian tradition of hānai by her childless maternal aunt, chiefess Grace Kamaʻikuʻi Young Rooke, and her husband, Dr. Thomas C.B. Rooke.

Queen Emma was born on January 2, 1836 in Honolulu and was often called Emalani (“royal Emma”). Her father was High Chief George Naʻea and her mother was High Chiefess Fanny Kekelaokalani Young.[1] She was adopted under the Hawaiian tradition of hānai by her childless maternal aunt, chiefess Grace Kamaʻikuʻi Young Rooke, and her husband, Dr. Thomas C.B. Rooke.

Emma’s father Naʻea was the son of High Chief Kamaunu and High Chiefess Kukaeleiki.[2] Kukaeleiki was daughter of Kalauawa, a Kauaʻi noble, and she was a cousin of Queen Keōpūolani, the most sacred wife of Kamehameha I. Among Naʻea’s more notable ancestors were Kalanawaʻa, a high chief of Oʻahu, and High Chiefess Kuaenaokalani, who held the sacred kapu rank of Kekapupoʻohoʻolewaikala (so sacred that she could not be exposed to the sun except at dawn).[3]:4

On her mother’s side, Emma was the granddaughter of John Young, Kamehameha I’s British-born military advisor known as High Chief Olohana, and Princess Kaʻōanaʻeha Kuamoʻo.[4] Her maternal grandmother, Kaʻōanaʻeha, was generally called the niece of Kamehameha I. Chiefess Kaʻōanaʻeha’s father is disputed; some say she was the daughter of Prince Keliʻimaikaʻi, the only full brother of Kamehameha; others state Kaʻōanaʻeha’s father was High Chief Kaleipaihala-Kalanikuimamao.[5][6] This confusion is due to the fact that High Chiefess Kalikoʻokalani, the mother of Kaʻōanaʻeha, married both to Keliʻimaikaʻi and to Kaleipaihala. Through High Chief Kaleipaihala-Kalanikuimamao she could be descended from Kalaniʻopuʻu, King of Hawaii before Kiwalaʻo and Kamehameha. King Kalākaua and Queen Liliʻuokalani criticized Queen Emma’s claim of descent from Kamehameha’s brother, supporting the latter theory of descent. Liliʻuokalani claimed that Keliʻimaikaʻi had no children, and that Kiilaweau, Keliʻimaikaʻi’s first wife, was a man.[7]:404 This was to strengthen their claim to the throne, since their great-grandfather was Kamehameha I’s first cousin. But even through the second line Queen Emma would still have been descendant of Kamehameha I’s first cousin since Kalaniʻopuʻu was the uncle of Kamehameha I. It can be noted that one historian of the time, Samuel Kamakau, supported Queen Emma’s descent from Keliʻimaikaʻi.[3]:357-358

Emma grew up at her foster parents’ English mansion, the Rooke House, in Honolulu. Emma was educated at the Royal School, which was established by American missionaries. Other Hawaiian royals attending the school included Emma’s half-sister Mary Paʻaʻāina. Like her classmates Bernice Pauahi Bishop, David Kalākaua and Lydia Liliʻuokalani, Emma was cross-cultural — both Hawaiian and Euro-American in her habits. But she often found herself at odds with her peers. Unlike many of them, she was neither romantic nor prone to hyperbole.[citation needed] When the school closed, Dr. Rooke hired an English governess, Sarah Rhodes von Pfister, to tutor the young Emma. He also encouraged reading from his extensive library. As a writer, he influenced Emma’s interest in reading and books. By the time she was 20, she was an accomplished young woman. She was 5′ 2″ and slender, with large black eyes. Her musical talents as a vocalist, pianist and dancer were well known. She was also a skilled equestrian.

Friends

Emma had many friends, a cosmopolitan group that included non-Hawaiians, hapa-haole (mixed race) and kānaka maoli (full blooded Hawaiians), who were mostly people she had met in her school days and her reign as Queen Consort. Prior to her education at Royal School, Emma had no childhood friends besides her cousin Peter Kaeo.[3]:67

- Princess Victoria Kamāmalu, two years younger than Emma, had been friends with her since school days. Their friendship grew after Emma became Victoria’s sister-in-law. Like Emma, she was a talented singer and pianist, and a devout Christian (although she was Calvinist and Emma was Anglican). Emma spent more time with Victoria than any other friend, since they attended the same family and official functions.

- High Chiefess Elizabeth Kekaaniau Pratt, a quarter Caucasian like Emma, was Emma’s roommate at Royal School. Emma referred to her as her “cousin Lizzy” since they were third cousins. They were born in the same year, but she outlived Emma by forty-three years. Elizabeth was a bridesmaid at Emma’s wedding and frequently was a lady-in-waiting.[8]

- Lucy Kaopauli Kalanikiekie Peabody, four years Emma’s junior, served as one of Emma’s maids-of-honor. Her mother was Elizabeth K. Davis, daughter of George H. Davis, son of Isaac Davis, the companion in arms of Emma’s grandfather, John Young. Emma’s father, Dr. Rooke, was once involved in a business partnership with Lucy’s father, Dr. Parker Peabody, an American physician.

- Mary Pitman, one of the queen’s bridesmaids, was her first cousin. Mary’s mother was the Chiefess Kinoʻole o Liliha from the Olaʻa region of Hawaii island, and the daughter of High Chief Hoʻolulu who concealed the bones of Kamehameha I in a secret hiding place. Mary’s father was American businessman Benjamin Pitman.

- Rebecca Gregg’s friendship developed out of the relationship that her husband had as an adviser and later minister to the king in spite of the king’s opposition to annexation by the United States. The Greggs were often guests in Kailua-Kona on Hawaii island and at their Nuʻuanu summer house. Rebecca was frequently present at court functions and a companion for rides with court ladies. She even named one of her daughters Emma.[3]:68

- Cornelia Hamlin, Gregg’s niece from California, accompanied them to Hawaii in 1853. She also accompanied the Greggs on their first audience with King Kamehameha II when they met Prince Alexander for the first time. It must have been shortly thereafter that Cornelia met Emma and became a close friend. When Cornelia married Captain William Babcock (a whaler) in Jan. 1857, both the king and queen attended the wedding. The king even gave away the bride. Gregg described Cornelia as being the “Queen’s most intimate friend”.

- Annie S. Parke, five years Emma’s senior, had easy access to the court because of her husband’s position. William Parke served both Kamehameha II and Alexander Liholiho as the kingdom’s marshal, until 1884. Annie chose the wedding trousseau for Emma and a wardrobe for Victoria on her trip to the U.S. mainland a few months before the wedding.

- Alice Brown was the niece of Sarah Von Pfister, Emma’s childhood governess. Her father was Thomas Brown, the royal gardener at Windsor Castle before he moved to Hawaii in 1844. Alice was an Anglican, devoted to her faith and to helping the poor and the sick. These qualities must have attracted Emma to Alice.

Emma had other female friends, such as Bernice Pauahi, her third cousin and schoolmate; Ruth Keʻelikōlani, her half-sister-in-law; Juliette Cooke, her old teacher; Sarah Von Pfister, her governess; Lydia Kamakaeha and Kapiʻolani, before 1874.

Close male friends included her cousin Peter Kaeo, who was diagnosed with leprosy; David Kalākaua, a classmate from school; Prince Lot, an old classmate and her brother-in-law; David Gregg, the American Commissioner; and Robert Crichton Wyllie, the minister of foreign affairs.[3]:69

Married life and reign

Emma and Queen Victoria silver christening cup

Emma became engaged to the king of Hawaii, Alexander Liholiho. At the engagement party, a Hawaiian charged that Emma’s Caucasian blood made her unfit to be the Hawaiian queen; her lineage was not suitable enough to be Alexander Liholiho’s bride. On June 19, 1856, she married Alexander Liholiho, who a year earlier had assumed the throne as Kamehameha IV. He was also fluent in both Hawaiian and English. Two years later on May 20, 1858 Emma gave birth to a son, Prince Albert Edward Kamehameha.

During her reign, the queen tended palace affairs, including the expansion of the palace library. During her reign and after, she was known for her humanitarian efforts. Inspired by her adoptive father’s work, she encouraged her husband to establish a public hospital to help the Native Hawaiians who were in decline due to foreign-borne diseases like smallpox. In 1859, Emma established Queen’s Hospital and visited patients there almost daily whenever she was in residence in Honolulu. It is now called the Queen’s Medical Center.

Prince Albert, who was always called “Baby” by Emma, had been celebrated for days at his birth and every public appearance. Mary Allen, wife of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Elisha Hunt Allen, had a son Frederick about the same age, and they became playmates. In 1862, Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom agreed to become godmother by proxy, and sent an elaborate silver christening cup. Before the cup could arrive, the prince fell ill in August and condition worsened. The Prince died on August 27, 1862. Her husband died a year later, and Emma would not have any more children.[9]

[edit] Names

After her son’s death and before her husband’s death, she was referred to as “Kaleleokalani”, or “flight of the heavenly one”. After her husband also died, it was changed into the plural form as “Kaleleonālani” , or the “flight of the heavenly ones”. She was baptized into the Anglican faith in October 21, 1862 as “Emma Alexandrina Franis Agnes Lowder Byde Rook Young Kaleleokalani.[3]:152

Queen Emma was also nicknamed “Wahine Holo Lio” in deference to her renowned horsemanship.

[edit] Religious legacy

Cornerstone of St. Andrew’s Cathedral layed in 1867

In 1860, Queen Emma and King Kamehameha IV petitioned the Church of England to help establish the Church of Hawaii. Upon the arrival of Anglican bishop Thomas Nettleship Staley and two priests, they both were baptized on October 21, 1862 and confirmed in November 1862. With her husband, she championed the Anglican (Episcopal) church in Hawaii and founded St. Andrew’s Cathedral, raising funds for the building. In 1867 she founded Saint Andrew’s Priory School for Girls.[10] She also laid the groundwork for an Episcopal secondary school for boys originally named for Saint Alban, and later ʻIolani School in honor of her husband. Emma and King Kamehameha IV are honored with a feast day of November 28 on the liturgical calendar of the U.S. Episcopal Church.[11][12]

[edit] Royal Election of 1874

After the death of King Lunalilo, Emma decided to run in the constitutionally-mandated royal election against future King David Kalākaua. She claimed that Lunalilo had wanted her to succeed him, but died before a formal proclamation could be made.

The day after Lunalilo died, Kalākaua declared himself candidate for the throne. The next day Queen Emma did the same. The first real animosity between the Kamehamehas and Kalākaua begun to appear, as he published a proclamation:

” To the Hawaiian Nation.”

“Salutations to You—Whereas His Majesty Lunalilo departed this life at the hour of nine o’clock last night; and by his death the Throne of Hawaii is left vacant, and the nation is without a head or a guide. In this juncture it is proper that we should seek for a Sovereign and Leader, and doing so, follow the course prescribed by Article 22nd of the Constitution. My earnest desire is for the perpetuity of the Crown and the permanent independence of the government and people of Hawaii, on the basis of the equity, liberty, prosperity, progress and protection of the whole people. It will be remembered that at the time of the election of the late lamented Sovereign, I put forward my own claim to the Throne of our beloved country, on Constitutional grounds — and it is upon those grounds only that I now prefer my claims, and call upon you to listen to my call, and request you to instruct your Representatives to consider, and weigh well, and to regard your choice to elect me, the oldest member of a family high in rank in the country. Therefore, I, David Kalakaua, cheerfully call upon you, and respectfully ask you to grant me your support.” D. KALAKAUA

Iolani Palace, Feb. 4, 1874.

Queen Emma issued her proclamation the next day:

“To the Hawaiian People:

” Whereas, His late lamented Majesty Lunalilo died on the 3rd of February, 1874, without having publicly proclaimed a Successor to the Throne; and whereas, ” His late Majesty did before his final sickness declare his wish and intention that the undersigned should be his Successor on the Throne of the Hawaiian Islands, and enjoined upon me not to decline the same under any circumstances; and whereas. “Many of the Hawaiian people have since the death of His Majesty urged me to place myself in nomination at the ensuing session of the Legislature; ” Therefore, in view of the foregoing considerations and my duty to the people and to the memory of the late King, I do hereby announce and declare that I am a Candidate for the Throne of these Hawaiian Islands, and I request my beloved people throughout the group, to assemble peacefully ad orderly in their districts, and to give formal expression to their views on this important subject, and to instruct their Representatives in the coming session of the Legislature. “God Protect Hawaii! ” “Honolulu, Feb. 5, 1874.

EMMA KALELEONALANI. “[3]:283

Emma’s candidacy was agreeable to many Native Hawaiians, not only because her husband was a member of the Kamehameha Dynasty, but she was also closer in descent to Hawaii’s first king, Kamehameha The Great, than her opponent. On foreign policy, she (like her husband) were pro-British while Kalākaua was pro-American. She also strongly wished to stop Hawaii’s dependence on American industry and to give the Native Hawaiians a more powerful voice in government. While the people supported Emma, the Legislative Assembly, which actually elected the new monarch, favored Kalākaua, who won the election 39 – 6. News of her defeat caused a large-scale riot, which was eventually dispersed due to the assistance of both British and American troops stationed on warships in Honolulu Harbor.

After the election, she retired from public life. While she would come to recognize Kalākaua as the rightful king, she would never speak with his wife Queen Kapiʻolani.

[edit] As Queen Dowager

After the death of her husband and son, she remained a widow for the rest of her life. Known affectionately as the “Old Queen”, King Kalākaua left a seat for her at any royal occasion, even though she rarely attended. Specific conspicuous events that Emma did not attend were:

- Liliʻuokalani’s birthday celebration at Aliʻiolani Hale

- Receptions for high foreign officials and guests (including American Admiral Stevens of the USS Pensacola and the new minister of Foreign Affairs)

- The laying of the foundation of Lunalilo Home.

Emma would never attend any event with either Liliʻuokalani or Kapiʻolani. This was because Emma had blamed the death of Albert on Queen Kapiʻolani, who was supposed to be the child’s governess.[citation needed]

Despite the great differences in their kingdoms, Queen Emma and Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom became life-long friends; both had lost sons and spouses. They exchanged letters, and Emma traveled to London in 1865 to visit and spend a night at Windsor Castle on November 27. Queen Victoria remarked of Emma, “Nothing could be nicer or more dignified than her manner.”[13]

On her way back, she had a reception given for her on August 14, 1866 by Andrew Johnson at the White House.[14] Some note this as the first time anyone with the title “Queen” had had an official visit to the U.S. presidential residence.[15]

Emma was known to be strongly against republicanism, she was once said:

“We have yet the right to dispose of our country as we wish, and be assured that it will never be to a Republic!”

[edit] Impressions

Queen Emma was warmly received by Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. The two widow queens sympathize with each other and Queen Victoria recodred in her journal on the afternoon of September 9, 1865:

“After luncheon I received Queen Emma, the widowed Queen of the Sandwich Islands or Hawaii, met her in the Corridor & nothing could be nicer or more dignified than her manner. She is dark, but not more so than an Indian, with fine feathers [features?] & splendid soft eyes. She was dressed in just the same widow’s weeds as I wear. I took her into the White Drawing room, where I asked to sit down next to me on the sofa. She was moved when I spoke to her of her great misfortune in losing her only child. She was very discreet & would only remain a few minutes. She presented her lady, who husband is Chaplain, both being Hawaiians….”[3]:199-200

Isabella Bird, on her travels to Hawaii, met Queen Emma and described her as very British and Hawaiian in many ways:

“Miss W. kindly introduced me to Queen Emma, or Kaleleonalani, the widowed queen of Kamehameha IV., whom you will remember as having visited England a few years ago, when she received great attention. She has one-fourth of English blood in her veins, but her complexion is fully as dark as if she were of unmixed Hawaiian descent, and her features, though refined by education and circumstances, are also Hawaiian; but she is a very pretty, as well as a very graceful woman. She was brought up by Dr. Rooke, an English physician here, and though educated at the American school for the children of chiefs, is very English in her leanings and sympathies, an attached member of the English Church, and an ardent supporter of the “Honolulu Mission.” Socially she is very popular, and her exceeding kindness and benevolence, with her strongly national feeling as an Hawaiian, make her much beloved by the natives.”[16]

in an interview, Kanahele, author of Queen Emma: Hawaii’s remarkable queen said :

“She was different from any of her contemporaries. Emma is Emma is Emma. There’s no one like her. A devout Christian who chose to be baptized in the Anglican church in adulthood, and a typically Victorian woman who wore widow’s weeds, gardened, drank tea, patronized charities and gave dinner parties, she yet remained quintessentially Hawaiian. She wrote exquisite chants of lament in Hawaiian, craved Hawaiian food when she was away from it, loved to fish, hike, ride and camp out (activities she kept up to the end of her life) and, throughout her life, took very seriously her role as a protector of the people’s welfare. In a way, she was a harbinger of things to come in terms of Hawaii’s multi-ethnic, multi-cultural society. You have to be impressed with her eclecticism — spiritually, emotionally and physically. She was kind of our first renaissance queen.”[citation needed]

MARK TWAIN

An Epistle from Mark Twain published in the Daily Hawaiin Herald 1866

San Francisco, Sept. 24th

THE QUEEN’S ARRIVAL.

Queen Emma and suite arrived at noon today in the P. M. S. S. Sacramento, and was received by Mr. Hitchcock, the Hawaiian Consul, and escorted to the Occidental Hotel, where a suite of neatly decorated apartments had been got ready for her. The U. S. Revenue cutter Shubrick went to sea and received the guest with a royal salute of 21 guns, and then escorted her ship to the city; Fort Point saluted again, and the colors of the other fortifications and on board the U. S. war steamer Vanderbilt were dipped as the Sacramento passed. The commander of the fleet in these waters had been instructed to tender the Vanderbilt to Queen Emma to convey her to the Islands when she shall have concluded her visit. the City government worried for days together over a public reception programme, and then, when the time arrived to carry it into execution, failed. But a crowd of gaping American kings besieged the Occidental Hotel and peered anxiously into every carriage that arrived and criticised every woman who emerged from it. Not a lady arrived from the steamer but was taken for Queen Emma, and her personal appearance subjected to remarks – some of them flattering and some otherwise. C. W. Brooks and Jerome Leland, and other gentlemen, are out of pocket and a day’s time, in making preparations all day yesterday for a state reception – but at midnight no steamer had been telegraphed, and so they sent their sumptuous carriages and spirited four-horse teams back to the stables and went to bed in sorrow and disappointment.

The Queen was expected at the public tables at dinner tonight, (in the simplicity of the American heart,) and every lady was covertly scrutinized as she entered the dining room – but to no purpose – Her Majesty dined in her rooms, with her suite and the Consul.

She will be serenaded tonight, however, and tomorrow a numerous cortege will march in procession before the hotel and give her three cheers and a tiger, and then, no doubt, the public will be on hand to see her if she shows herself.

ALPHABET WARREN.

I believe I do not know of anything further to write about that will interest you, except that in Sacramento, a few days ago, when I went to report the horse fair of the State Agricultural Society, I found Mr. John Quincy Adam Warren, late of the Islands, and he was well dressed and looked happy. He had on exhibition a hundred thousand varieties of lave and worms, and vegetables, and other valuables which he had collected in Hawaii-nei. I smiled on him, but he wouldn’t smile back again. I did not mind it a great deal, though I could not help thinking it was ungrateful in him. I made him famous in California with a paragraph which I need not have written unless I wanted to – and this is the thanks I get for it. He would never have been heard of if I had let him alone – and now he declines to smile. I will never do a man a kindness again.

MISCELLANEOUS.

Charles L. Richards, of Honolulu, sails tomorrow for the Islands with a fast team he purchased here.

The steamer Colorado is undergoing the alterations necessary to fit her for the China Mail Company’s service, and will sail about the first of January with about all the cabin passengers she can carry. She will touch at Honolulu, as I now understand. I expect to go out in her, in order to see that everything is done right. commodore Watson is to command her I believe. I am going chiefly, however, to eat the editor of the Commercial Advertiser for saying I do not write the truth about the Hawaiian Islands, and for exposing my highway robbery in carrying off Father Damen’s book – History of the Islands. I shall go there might hungry. Mr. Whitney is jealous of me because I speak the truth so naturally, and he can’t do it without taking the lock-jaw. But he ought not to be jealous; he ought not to try to ruin me because I am more virtuous than his is; I cannot help it – it is my nature to be reliable, just as it is his to be shaky on matters of fact – we cannot alter these natures – us leopards cannot change our spots. Therefore, why growl? – why go and try to make trouble? If he cannot tell when I am writing seriously and when I am burlesquing – if he sits down solemnly and take one of my palpable burlesques and reads it with a funereal aspect, and swallows it as petrified truth, – how am I going to help it? I cannot give him the keen perception that nature denied him – now can I? Whitney knows that. Whitney knows he has done me many a kindness, and that I do not forget it, and am still grateful – and he knows that if I could scour him up so that he could tell a broad burlesque from a plain statement of fact, I would get up in the night and walk any distance to do it. You know that, Whitney. But I am coming down there might hungry – most uncommonly hungry, Whitney.

MARK TWAIN.

Death and legacy

In 1883, Emma suffered the first of several small strokes and died two years later on April 25, 1885 at the age of 49.

At first she was laid in state at her house; but Alexander Cartwright and a few of his friends moved the casket to Kawaiahaʻo Church, saying her house was not large enough for the funeral. This was evidently not popular with those in charge of the church, since it was Congregational; Queen Emma had been a supporter of the Anglican Mission, and was an Episcopalian. Queen Liliʻuokalani said it “…showed no regard for the sacredness of the place”. However, for the funeral service, Bishop Willis of the English Church officiated in the Congregational church with his ritual. She was given a royal procession and was interred in the Royal Mausoleum of Hawaii known as Mauna ʻAla, next to her husband and son.[7]:108–109

The Queen Emma Foundation was set up to provide continuous lease income for the hospital. Its landholding in the division known as the Queen Emma Land Company include the International Marketplace and Waikiki Town Center buildings.[17][18] Some of the 40 year leases expire in 2010.[19] The area known as Fort Kamehameha in World War II, the site of several coastal artillery batteries, was the site of her former beach-front estate. After annexation it was acquired by the U.S. federal government in 1907.[20]

The Emalani festival, Eo e Emalani i Alakaʻi held in October on the island of Kauaʻi in Koke’e State Park celebrates an 1871 visit. [21]