PFAFF’S CELLAR

“The vault at Pfaffs where the drinkers and laughers meet to eat and drink and carouse while on the walk immediately overhead pass the myriad feet of Broadway.” –Walt Whitman–

Charles Pfaff’s beer cellar in lower Manhattan was a magnet for some of the most unconventional and creative individuals of nineteenth-century New York City, including Walt Whitman, poet and actress Adah Isaacs Menken, journalist and social critic Henry Clapp, playwright John Brougham, Fitz-James O’Brien, Bayard Taylor, William Winter, George Arnold, Louis Gottschalk and artist Elihu Vedder. Located at 653 Broadway a few doors south of the Winter garden, modeled on the German Rathskellers that were booming in Europe, above Bleecker Street in New York City, during the 1850s. In 1860, William Dean Howells and Ralph Waldo Emerson visited Whitman at Pfaffs, but found it a bit too raucous for their taste.

The bar, known simply as “Pfaff’s,” was hailed as the “favorite resort of all the prominent actors, authors, artists, musicians, newspaper men, and men-about-town of the time” (“In and About” 2). It was decorated “in a plain, quaint fashion, with an estrade, but the service was clean and the cooking excellent, and it soon made a reputation that brought it hundreds of dollars’ worth of daily custom” (“In and About” 2). He set up long tables in the dark recesses of the cellar, a vault like space that was under the sidewalk of Broadway above. The work of Poe, recently deceased, made him the group’s spiritual mentor. But the real shining star of Pfaff’s was the very much alive, Walt Whitman

Pfaff  accepted his female clientele like Ada Clare and others associated with the group “with a bland smile, paying no attention to the shocked gossip on the street. He was a respectable man of business, but not a one of the customers remarked about Pfaff and his helpers: ‘The Germans are not shocked when a woman enters a restaurant'” (A. Parry 21). Artist Elihu Vedder contends that Pfaff enjoyed the Bohemian circle’s patronage beyond the revenue they brought to his establishment: “I really believe Pfaff himself loved the Boys. The time came when he retired to the country well off; but then the time also came when he returned and started another place further up-town. I saw him in his new place… He said he was well off, but that he could not stand the country; he had to do something; but then he said, ‘It isn’t the same thing; dere’s no more boys left enny more.’ I have come to think that myself” (Digressions 226).Pfaff was a German from Switzerland and he “was rotund of form though devoid of excessive fat. His big head was crowned with short and bristling hair and lit up by a silent yet jovial smile. Like most proprietors of cafés chosen by literati for their headquarters he was not learned but he knew how to behave. He took pride in his beers and wines and still more in his bookish and eccentric clientele. Shrewdly, he was aware of the profitable growth of his reputation as a patron of American belles lettres. He fostered his fame unobtrusively and skillfully. He drank to the toasts of his guests at their invitation. He listened to their tales and verse with a sweet and quiet dignity. He kept his cellar open into the dawn for the sake of a handful of Bohemians engaged in a verse-making contest.

accepted his female clientele like Ada Clare and others associated with the group “with a bland smile, paying no attention to the shocked gossip on the street. He was a respectable man of business, but not a one of the customers remarked about Pfaff and his helpers: ‘The Germans are not shocked when a woman enters a restaurant'” (A. Parry 21). Artist Elihu Vedder contends that Pfaff enjoyed the Bohemian circle’s patronage beyond the revenue they brought to his establishment: “I really believe Pfaff himself loved the Boys. The time came when he retired to the country well off; but then the time also came when he returned and started another place further up-town. I saw him in his new place… He said he was well off, but that he could not stand the country; he had to do something; but then he said, ‘It isn’t the same thing; dere’s no more boys left enny more.’ I have come to think that myself” (Digressions 226).Pfaff was a German from Switzerland and he “was rotund of form though devoid of excessive fat. His big head was crowned with short and bristling hair and lit up by a silent yet jovial smile. Like most proprietors of cafés chosen by literati for their headquarters he was not learned but he knew how to behave. He took pride in his beers and wines and still more in his bookish and eccentric clientele. Shrewdly, he was aware of the profitable growth of his reputation as a patron of American belles lettres. He fostered his fame unobtrusively and skillfully. He drank to the toasts of his guests at their invitation. He listened to their tales and verse with a sweet and quiet dignity. He kept his cellar open into the dawn for the sake of a handful of Bohemians engaged in a verse-making contest.

Adah Isaac Menkin

Adah Isaacs Menken (1835-1868)

Adah was another Pfaff luminary. She was an author, poet, painter, actress and enigmatic figure, exotic and risque, an actress known throughout the world for her sensual, scandalous stage performances who also happened to be married to the world heavyweight champion, Johnnie Heenan. She was mysterious, a woman of mixed heritage, born in New Orleans, who guarded her cultural roots (and African-American blood) by spinning exotic tales about her background and childhood upbringing.

Adah was another Pfaff luminary. She was an author, poet, painter, actress and enigmatic figure, exotic and risque, an actress known throughout the world for her sensual, scandalous stage performances who also happened to be married to the world heavyweight champion, Johnnie Heenan. She was mysterious, a woman of mixed heritage, born in New Orleans, who guarded her cultural roots (and African-American blood) by spinning exotic tales about her background and childhood upbringing.

Her book of poetry, “Infelicia,” was dedicated to Charles Dickens, one of her mentors.

In 1859 she appeared on Broadway in the play “The French Spy. Once again, her work was not highly regarded by the critics. The New York Times described her as ‘the worst actress on Broadway’. The Observer said “she is delightfully unhampered by the shackles of talent”. She converted to Judaism and married a Jewish musician, Alexander Isaac Menken. The commentators continued to be cynical, saying that a marriage to a rich husband was the only way to sustain a flagging (acting) career. The marriage to Alex Menken was short-lived. Alex Menken separated from and later divorced Adah, though she remained committed to Judaism her entire life. She had four marriages in the space of seven years. (Wikepedia)

In Albany, Menken’s manager Edwin James called the first press conference. He lured his fellow journalists up the Hudson to gape at the beauty whose star quality struck them like a bolt of lightning.

James, a former lawyer, currently theater-sports reporter on the New York Clipper, mustered representatives from New York’s six daily newspapers, three weeklies and two monthlies. Mazeppa opened three months after Lincoln’s inauguration. The Civil War may have been heating up, but the “naked lady” captured front page attention. James could boast of notoriety in his own right. An Englishman, he provided the model for Stryver, the crooked barrister in Charles Dickens’s Tale of Two Cities. James may have had a shady past, but he remained Menken’s truest friend, the only one to stand fast when flatterers eager to drink champagne at her expense in flush times abandoned her in adversity.

Journalists followed James and a liveried servant into Menken’s suite, the most expensive in Albany. Not one scribbler regretted the tedious trip after Menken, reclining on a tiger skin, showed her much vaunted muscular legs. She sipped champagne in between feeding bon bons to a French poodle. The petit bombshell (about five feet), fancied herself the successor to Lola Montez whom she surpassed in popularity. In homage to Lola, Menken choreographed a “spider dance” based on the scandalous shimmy her mentor brought down the house with.

Menken fielded questions like seasoned politician. Truth be dammed, as long as her glamorous image wowed them. One secret she could not make public during the racial hysteria of the Civil War : her birth. A New Orleanian, born in 1835, Adah Bertha Theodore had a black father. Her Jewish mother and an Irish ancestor tossed into the gumbo gave her a multicultural pedigree before the fashion.

When in San Francisco, Brett Harte asked her whether it was true that she lived with Sam Houston in Texas as his “adopted daughter”, she batted her violet eyes and answered, “It was General Jackson and Methuselah and other big men.” If provoked, she fired rockets like, “Good women are rarely clever and clever women are rarely good.”

Menken turned the Albany interview from her romances to her acting triumphs. She proclaimed her affinity for Lord Byron, another rebellious soul, whom she emulated by wearing curls and a white, high collared blouse. The gentlemen of the press looked at each other, then to James for clarification. Had the dashing Englishman adapted his poem about the historical figure Mazeppa into play form as a vehicle for the American beauty? Menken knew this idea was nonsense; however, she smiled in a superior way to add to the reporters’ confusion.

At the end of the interview, Menken drove the reporters wild. She announced, “I must regretfully leave you. The wild steed must be tamed daily.” James ushered his panting colleagues out of the star-to-be’s presence. Menken showed no traces of an accident that almost nipped her career n the bud.. Earlier, at rehearsal, Menken confused her trained horse by changing his customary starting position at the footlights. Belle Beauty zoomed part way up the ramp, only to crash down on planks below. Knocked unconscious, blood spurted from Menken’s shoulder. Typically, Menken refused to show the “white feather” (to “show the white feather” is to display cowardice). Revived, if pale as death, she drew the straps around her, accomplishing the stunt this time to the amazement of onlookers.

Mazeppa-Menken, a Tartar prince, first appeared onstage, a regal figure in black velvet cloak and tights ready for swashbuckling and dueling. At Mazeppa’s climax, a gang of enemy soldiers apparently strip our hero-heroine nude. Tied to the back of a snorting steed, storm raging, Menken clattered up a cardboard mountain over a narrow plywood ramp ending on the “flies” four stories up. This pioneering striptease act kept Menken in the limelight throughout her brief career.

After being anointed in Albany, Menken swept San Francisco, Virginia City, London and Paris. Mazeppa’s popularity surpassed and continued longer than the didactic Uncle Tom’s Cabin of the same era. On 23 March 1866, the superstar returned to New York. George Wood, manager of the Broadway theater, capitulated to her astronomical salary demands. He had no choice, for the toast of Frisco and Europe brought rave reviews from discerning critics like Mark Twain, a friend and admirer. In 1864 Twain, who worked as a fledgling newspaper reporter for the Californian, witnessed the Menken bring down the house. His inimitable prose described how “A magnificent spectacle dazzled my vision—the whole constellation of the Great Menken came flaming out of the heavens like a vast spray of gas jets, and shed a glory abroad over the universe as it fell.”

Off to demolish the British champion, Heenan left the pregnant Adah in New York. By January, news of this marriage of beauty and brawn, foreshadowing Marilyn Monroe’s to Joe DiMaggio, leaked out. “Itemizers” pounced on this scandal about to happen. Rumors sprung up that the couple were not legally married. Pro and con reporters split into factions to fight it out in tabloid newspapers.

The pot came to a full boil when Menken’s first husband chimed in that she committed bigamy, denying she obtained a valid divorce from him. This public ridicule damaged Adah’s career, not to mention her sanity. The solitary voice of Frank Queen, chief editor of the Clipper, took Adah’s side. He complained that “The association of her name with John Heenan has made her the target for almost every newspaper scribbler in the country, who have severally married her to Tom Thumb, Jas. Buchanan and the King of the Cannibal Islands.”

While New Yorkers acclaimed Heenan for his boxing prowess, they denounced Adah as an immoral, depraved female. Adah refused to believe her husband’s perfidy. A trooper, Adah made game attempts at acting engagements. The following June her son was born, only to die in a few weeks. Adah wound up in court for non payment of rent. Heenan not only refused to pay the bill, but his lawyer called her a prostitute. When she finally sued Heenan for divorce, He hotly denied Menken’s claim on him in New York’s newspapers. Heenan announced, “The woman calling herself my wife . . . is an impostor.”

Adah retreated to Jersey City where she attempted suicide. An unknown friend, possibly Walt Whitman, found her in time and saved her. In 1860, Adah assuaged her heartache by writing her most gut wrenching poetry. Erica Jong, in a review she wrote of Sylvia Plath’s Correspondence in November 1975, pointed out that “Sylvia Plath’s poetry was the first poetry by a woman to fully express the female rage.” Interestingly, Menken raged more than a century before Plath. Moods of despair alternated with defiant ones. In Judith, published in September 1860 in the Sunday Mercury, Menken blasted Heenan in a Biblical context. An admirer of Menken’s poetry, Robert Henry Newell, the influential literary editor of the Sunday Mercury, became her third husband in September 1862. Newell attained nationwide prominence during the Civil War under the pseudonym of Orpheus Kerr. President Lincoln chuckled over his satires about corrupt office seekers in Washington. In October 1860, Newell published another Menken essay favoring the emancipated woman. Menken demanded that “daughters should be trained with higher motives than that of being fashionable and securing wealthy husbands. There are other missions for women than that of wife or mother.”

(www.popmatters.com)

Not until 1938 were the probable facts of her birthplace and paternity established. Prior to that time she was variously reported to have been born in New York, Havana, and a half-dozen other places. She was said to have been born of a distinguished, old Southern family; another account claimed she was born in Arkansas of a French mother and an American-Indian father. Throughout the years of her life she consistently confused the issue by telling conflicting and varying stories, partly because she was ashamed of her parentage and partly because she was an actress always playing a role. The likeliest facts seem to be that Menken was born in New Orleans on June 15, 1835, that her mother was a very beautiful French Creole, that her father was Auguste Theodore, a highly respected “free” Negro of Louisiana.

She danced, when a child, in the ballet of the French Opera House in New Orleans. She was exceedingly bright; an exceptional scholar. She spoke French and Spanish fluently; she painted, wrote poetry that was of good quality and brought her earl y recognition. From New Orleans she went, while still a child, to Havana, danced there, and was crowned queen of the Plaza. Then she forsook the ballet and turned to the stage and, on tour, landed in Texas. And in Texas, at the age of twenty-one, she married a very handsome and distinguished musician, Alexander Isaac Menken.

y recognition. From New Orleans she went, while still a child, to Havana, danced there, and was crowned queen of the Plaza. Then she forsook the ballet and turned to the stage and, on tour, landed in Texas. And in Texas, at the age of twenty-one, she married a very handsome and distinguished musician, Alexander Isaac Menken.

She adored Menken, and Menken worshipped her. But with the characteristics and traditions of his Jewish forebears, Menken wanted a wife, a home, a family. Adah was not at all interested in home or family; in fact, the only thing she shared sincerely with him was his religion–she adopted the Jewish faith and remained steadfast in it until her death. But as for home life–no. Adah preferred the adulations of her audience and the adoration of the young men who gathered at the stage door, arms heavy with roses. Menken swallowed his jealous pride as long as he could, but when Adah insisted on smoking cigarettes in public, that was the last straw. Ladies did not smoke! Menken left her.

So Adah Menken went her exciting way from town to town, and men fell in love with her and her poetry, with her intellect and her lovely face and her exquisite figure. And rather than see them unhappy, she was generous in her love.

In New York she met the Benicia Boy. He was a strong, a brutal man, not unattractive in his strength. His fame as a pugilist had traveled ahead of him, and Adah was fascinated. She married him. On their honeymoon the Benicia Boy taught her to box; she soon learned to hold her own when they sparred good-humoredly. But after a month of marriage the good humor went out of it, and Heenan made a practice of beating Adah every night after dinner. So she divorced him.

But then scandal broke. Search of the records showed that before marrying the Benicia Boy she had neglected to divorce Menken. She was quite, innocent about it all; she had assumed it was the duty of the man of the family to attend to legal matters, including such details as divorce. But now the scandalmongers declared her a bigamist. Menken heard of the scandal, did the gentlemanly thing and divorced her, and everybody was happy.

Then Adah Menken gave birth to the Benicia Boy’s son, and the baby died at birth. She had wanted, longed for, adored that baby. Its death, and the scandals, and her two marriages and divorces–all these coming swiftly one upon the other–were forerunners of a long period of tragic sorrow and failure. But never discouragement,– she would never give up. She starved in New York. She gave readings from Shakespeare. She gave lectures on the life of the times. She had a boyish figure and she always wore her hair short–so, suddenly she appeared as Mr. Bones, blackface, in a minstrel show. Then, on the variety stage, she created a sensation by impersonations of Edwin Booth as Hamlet and Richelieu. But something–something truly sensational had to be done to make the public fully aware of her.

She met Blondin. Blondin was the brave gentleman who crossed the whirlpools of Niagara Falls on a tightrope. Blondin was enraptured by the beauty of the Menken. He wooed her, and she said perhaps–perhaps she would marry him if he would let her dance on the tightrope above Niagara with him–a husband-and-wife act.

Blondin said, “No.” He was afraid Adah’s beauty would distract him when he was above the whirlpool and he would fall to his death. No, he would do no tightrope act with the Menken. So they went on a vaudeville tour together.

That tour ended and Blondin went his way and Adah went hers, and hers led to the door of her business manager, Jimmie Murdock. Adah told Jimmie, who adored her, that she wanted to be a great tragedienne–or a great comedienne–or both. She wanted to play Lady Macbeth. and–or–Lady Teazle. Jimmie Murdock, something of a diplomat, told her she was too great to play Lady Treazle and not great enough to play Lady Macbeth, but that, because her boyish figure was so lovely and there was such fire in her voice and eyes, she should play in Mazeppa, the drama that was attracting some attention on Broadway. The story was based on the poem of Lord Byron. At the thrilling climax of the play, the noble Tartar lad, stripped of his clothes by his captors and bound to the back of a wild horse, dashed out of the wings up to the papier-mâché cliffs and disappeared in the clouds, while the audience grew hysterical with apoplectic applause.

It had been a tradition that during the ride of the barebacked horse, a stuffed dummy, naked and resembling Mazeppa, would be used. Menken would have no stuffed dummy. She would ride the horse herself. She would wear skin-tights. No matter how it shocked the audience that had never seen an actress in tights, she would play the role with dramatic realism; she would wear tights. So she wore tights. The audience was shocked–scandalized–horrified–and delighted! But New York was too stilted, too smug, too proper truly to appreciate great art. And Adah Menken said, “I’ll go to the one place where the audience demands real art; I’ll go to San Francisco.”

On August 24, 1863, that supreme master of San Francisco’s theatrical history, Tom Maguire, announced and presented at Maguire’s Opera House the great Menken in the daring, the sensational, the unprecedented Mazeppa in which “Miss Menken, stripped by her captors, will ride a fiery steed at furious gallop onto and across the stage and into the distance.”

According to the San Francisco papers of the next day, that night all the streets leading to Maguire’s Opera House were thronged with the most elegant of the city’s elite.

According to the San Francisco papers of the next day, that night all the streets leading to Maguire’s Opera House were thronged with the most elegant of the city’s elite.

Ladies in diamonds and furs rode up in handsome carriages; gentlemen in opera capes and silk hats were their attendants. It was a first night such as the city had never before seen. And when (again quoting the San Francisco papers), at climax of the play, the Menken vaulted to the back of her full-blooded California mustang and, clad tights with hair streaming down her back, raced her steed at mad pace across the mountains of Tartary, the enthusiasm of the audience was a mad frenzy never to be forgotten. So thrilling was the performance that it was said that on the opening night the leading man, Junius Booth–brother of Edwin–stood in the wings and completely forgot his lines.

Among the young men in the audience that night, and night after night that followed, were the three friends–Bret Harte, Joaquin Miller, and Charles Warren Stoddard. And these three, and scores of others, fall in love with Adah Menken, and it was even whispered that she was lavish with her love in return. But of all her admirers, she smiled on the young American humorist, Robert Henry Newell, and he became her third husband.

Bohemian San Francisco took Adah Menken to its gay and ample bosom, She was an actress and it loved actresses; she was a painter, and it loved artists; and, above all, she was a poetess, and it adored poets and poetesses. wherever you went, to whomever you talked, the two favorite topics of conversation in San Francisco–topics of equal importance –were the progress of the Civil War and the success of Adah Isaacs Menken.

Her fame increased. Imitators sprang up. In fact, one of these was Big Bertha, the circus fat lady who had played Juliet opposite Oofty Goofty’s Romeo at the Bella Union. Big Bertha played Mazeppa in pink tights, strapped to the back of a donkey. But one night the donkey, with huge Bertha astride him fell over the footlights into the theater pit, and the career of Bertha as Mazeppa ended.

Adah Menken’s marriage to Robert Newell lasted two years. Then she divorced him and married Mr. James Barkley about whom little is known. After all, none of her husbands was important in the life of Adah Menken.

And San Francisco went on adoring her, the San Francisco that had adopted her as its favorite daughter. The St. Francis Hook and Ladder Company made her a member of its fire-fighting brigade; she was presented with a beautiful fire belt, and the entire brigade, accompanied by a brass band, serenaded her. Her world was at her feet.

And then, quite suddenly the Menken decided she wanted new worlds to conquer. She took Mazeppa to Paris and London. During the tour she fell in love with, and was adored by, Alexandre Dumas, pére. Dumas, fils, threatened to horsewhip his father for being a senile Romeo. So Menken left Dumas and went to London.

She played Mazeppa, and London went wild. Charles Dickens fell in love with her; Charles Reade fell in love with her; Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Tom Hood, and a score of others wooed her. And, as always, the Menken was generous with her love. Life was full and rich and exciting.

But the tide turned. Ill health, the fruit of dissipation, wasted her away. She had made a fortune; her great wealth disappeared, and she lived in comparative poverty. In London, desperately in need of funds, she published her volume of Victorian poems and realized a few dollars.

London was cold, unfriendly. She returned to Paris and Paris had found new loves.

Faithful to her adopted religion, she spent her last hours speaking of life and faith and hope to a friendly rabbi. Then she wrote a brief note to an acquaintance. It was her hail and her farewell. She wrote, “I am lost to art and life. Yet, when all is said and done, have I not at my age tasted more of life than most women who live to be a hundred? It is fair, then, that I should go where old people go.”

Then she died. She was thirty-three years old. Her passing was unmarked, save for a brief eulogy in verse that appeared in a Paris paper:

Ungrateful animals, mankind;

Walking his rider’s hearse behind,

Mourner-in-chief her horse appears,

But where are all her cavaliers?John Heenan was one of the most famous and popular figures in America at the time, particularly on the east coast and especially in New York, his home town. The press were quick to point this out as they continued to accuse her of marrying solely to maintain her celebrity status. However, everyone that knew her well said that she genuinely loved the gregarious and outgoing Heenan.She played “Mister Bones,” a minstrel character, and impersonated Edwin Booth as Hamlet and Richelieu. She performed with Blondin, a Niagara Falls tightrope walker. Her provocative stage performance, strapped to a horse bareback, wearing only tights in Mazeppa, helped establish her reputation as a scandalous figure. On August 24, 1863, the master of San Francisco theater, Tom McGuire presented Mazeppa with Miss Menken. She later became Mrs. Robert Henry Newel. Even later she became Mrs. James Barkley. The probable facts of her life were not established until 1938.

She went to perform in Paris, France and was romanced by Alexandre Dumas, père. She went to London, England, and was wooed by Charles Reade, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Algernon Charles Swinburne, and

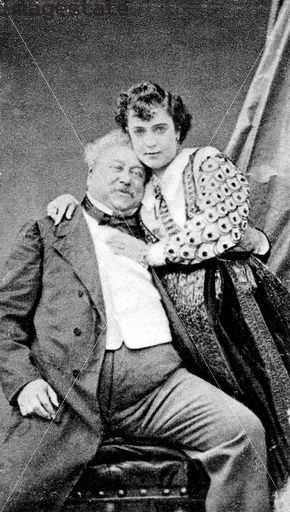

irca 1880: English poet and critic Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837 - 1909) with his friend, actress Adah Isaacs Menken. (Photo by Beard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Tom Hood, and became a friend to Charles Dickens. Rosetti is said to have offered her ten pounds to seduce Swinburne away from his fetish for flagellation, but that after six weeks she admitted defeat and returned the money.[1][2]

Later, in ill health, she wrote to a friend, “I am lost to art and life. Yet, when all is said and done, have I not at my age tasted more of life than most women who live to be a hundred? It is fair, then, that I should go where old people go.” She died at the age of thirty-three in Paris, France in 1868 and is interred in the Cimetière du Montparnasse.

Amos Bronson Alcott

(November 29, 1799 – March 4, 1888) was an American teacher, writer and philosopher who left a legacy of forward-thinking social ideas. His status as a well-publicized figure from the 1830s to the 1880s stemmed from his founding of two short-lived projects, an unconventional school and an utopian community known as “Fruitlands“, as well as from his association with the philosophy of Transcendentalism[1] and from the celebrity accruing to his friendship with Walt Whitman and the rising fame of his middle daughter, Little Women author Louisa May Alcott.[1] (Wikepedia and

In Spring 1830, at the age of 30, he married 29-year-old Abby May,[3] the sister of reformer and abolitionist Samuel J. May. Alcott was himself a Garrisonian abolitionist, and pioneered the strategy of tax resistance to slavery, which Henry David Thoreau made famous in Civil Disobedience.[4] Alcott publicly debated with Thoreau the use of force and passive resistance to slavery; along with Thoreau he was among the financial and moral supporters of John Brown and occasionally helped fugitive slaves escape via the Underground Railroad.

Research material:

Fast Monday links « voiletkay

Mar 26, 2010 @ 10:30:34